This detail from a 1948 Geological Survey map shows the rail and waterways around the entrance to the Buffalo harbor. The Michigan Avenue and Ohio Street bridges are highlighted (orange); the only practical way for motorists to reach the southern waterfront prior to the Skyway’s construction. The future path of the Skyway is also shown (green).

Map of Buffalo, NY. United States Geological Survey, 1948

In his cultural biography of the Buffalo Skyway (American Studies, Spring 2007), William Graebner argues that the winding, elevated roadway is as representative of Buffalo’s post-war mood as the art deco City Hall is of 1920’s optimism or the Olmstead parks and parkways of the city’s Gilded Age. It was a period which found the city “poised between its glorious past and a ‘rust belt’ future it could not yet see or feel. . . .” Over half a century later the “mood” is gone for many, as politicians, planners and the public at large debate the Skyway’s future.

By the mid-twentieth century, a high-level roadway connecting the City of Buffalo to the southern lakeshore was seen as a progressive solution to a number of traffic issues. As early as the 1920s, concerns had been expressed about the motor congestion in the city. As the volume of automobile traffic increased, Buffalo, like other Great Lakes metropolises such as Chicago, Cleveland and Milwaukee, needed to reconcile the needs of motorists with the realities of rail- and water-borne commerce. In the wake of the Second World War, Buffalo’s population was peaking, as arguably was America’s fascination with driving and the automobile. However, the combination of waterways and rail lines forced vehicular traffic looking to move in or out of the city through a limited number of paved arteries.

The situation was perhaps most acute for motorists traveling the lakeshore route to and from the southwest. Workers commuting to the mills and factories of Lackawanna and Blasdell faced a series of rail and water obstacles; the New York Central, the Buffalo River, and the City and Union Ship Canals. Limited to Michigan Avenue and Fuhrman Boulevard, they faced huge delays at the lift bridges and railroad crossings. Michigan Avenue in the 1950s witnessed “almost daily, serious jams” according to the Buffalo News, and those attempting to cross the Union Ship Canal at the end of a workday could expect to take half an hour to traverse the mile-long stretch of Fuhrman Boulevard between Ridge Road and Tifft Street.

The solution to this congestion problem was the Buffalo Skyway; over a mile of elevated roadway, which towered more than 100 feet above the rails and waterways. As it provided a utilitarian solution to the long-standing traffic issue, so too did it captivate the region’s inhabitants with its graceful, modern lines and its breathtaking vistas. When the Skyway opened in October 1955, the voices of praise were quick and plentiful. One motorist commented that “the view is terrific.” The Buffalo News editorialized that it gave “a special pleasure to anyone who ever got tangled up in any of the traffic jams down below,” along with “a completely new and breathtakingly sweeping panoramic view of what somehow seems a much greater city from ‘way up there.’”

The Skyway was the creation of engineer Edward P. Lupfer, whose previous local work included both the Peace Bridge and the Rainbow Bridge in Niagara Falls. Unlike many engineers of the period, who approached such projects from a purely utilitarian perspective, Lupfer strove to mix technology and science with a more artistic approach, reflecting his academic background in the humanities. Graebner suggests that the reinforced concrete design, labeled a “ribbon of steel and concrete” by reporter Ralph Wallenhorst, was reflective of the high modernism of the mid-1950s. With the decline of Buffalo’s harbor and southern lakeshore industry, the elevated highway which linked city and industry and rose above their obstacles is now seen by some as an obstacle itself; an obstacle to a revitalized waterfront and lakeshore. Has the solution now become the problem, or is demolition simply the latest panacea offered up as a remedy for economic decline? As the debate continues, perhaps these photos will serve to recapture some of the initial euphoria surrounding the Skyway, as well as some reflections of the mid-20th century world which served to create it.

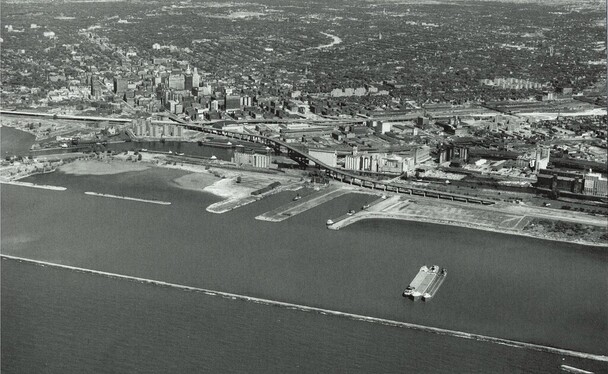

Before the Skyway – An aerial view looking northwest to the Buffalo harbor entrance from the 1940s. The Michigan Avenue bridge is in the central foreground.

Western New York Heritage

A view of the Michigan Avenue lift bridge, prior to 1939. The need to raise the bridges to allow the passage of shipping in and out of the harbor was the cause of “almost daily, serious jams” for traffic traveling between the city and the southern lakeshore. In this image, a dredging boat is passing underneath the bridge while a canal boat is tied up at right.

Western New York Heritage

Construction begins—In this aerial view from July 1954, the concrete pylons have been raised for the Skyway’s path around Buffalo Memorial Auditorium (center) and work has begun on the northern approach ramp paralleling Terrace and Franklin Streets.

Western New York Heritage

The old and the new—The Michigan Avenue bridge over the City Ship Canal in the right foreground us dwarfed by the new, modern Skyway in this view from the mid-1950s.

Western New York Heritage

“A thrill I’ll never forget. . . . There is breath-taking beauty in every direction—all this and time-saving too.” Motorists experience the Skyway shortly after its opening in 1955.

Western New York Heritage

Buffalo harbor with the Skyway in the background, ca. 1962. Note the extensive freighter traffic in the City Ship Canal and the 600-foot freighter (two football fields long!) in the Buffalo Dry Dock.

Western New York Heritage

A southerly view of Buffalo harbor and the lakeshore from the late 1950s. Several 1830s-vintage buildings still remain on lower Main Street, as does the Lehigh Valley Terminal, across from the Aud. This image clearly shows the Skyway turning to avoid the famous, now demolished, Dakota elevator with the “Gold Medal Flour” sign (right center).

Western New York Heritage

A “ribbon of steel and concrete.” These two panoramic views from the early 1960s track the Skyway’s route across Buffalo’s harbor entrance. Note the progress being made on the Niagara Section of the New York State Thruway (I-190) in the center of both images, where the paved section is nearing what will become the Louisiana Street exit.

Western New York Heritage