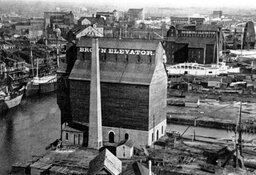

Buffalo's wooden elevators were opportunistic wonders of design and invention. They bridged the time gap between the age of wooden sailing vessels and the architecture of 20th century modernism.

Old Photo Album: A Forgotten Atlantis

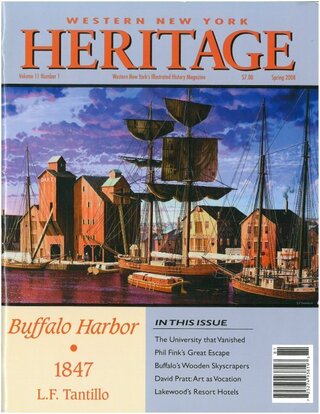

The full content is available in the Spring 2008 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content