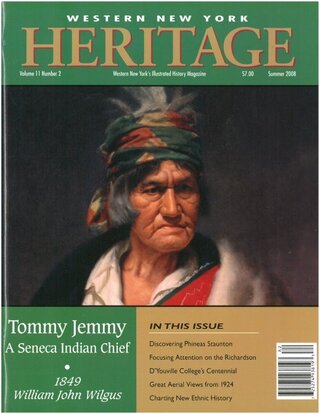

Tommy Jemmy, A Seneca Indian Chief, painted from life about 1849, oil on canvas, by William J. Wilgus.

Private Collection

Buffalo-born artist William John Wilgus (1819-1853) painted several portraits of Western New York Indians. Unfortunately most of the works were lost in a fire that destroyed the house of a collector in Lyons, NY. The best portrait of all, that of Tommy Jemmy, was not in the fire. That 1849 portrait was considered an epitome of its genre, but in 2005 its whereabouts were unknown. According to the late Chase Viele’s notes, it had been last on public view in Buffalo during the 1940s at the Albright Art Gallery; but the Albright-Knox had no record of such an exhibit. Chase thought the work was owned by Dartmouth University but their curator was completely unaware of the painting. Thus, it was with some excitement that I discovered the painting had survived in excellent condition as the treasure of a private collector. The owner has generously agreed to share the image with our audience.

Buffalo Creek Seneca Chief Tommy Jemmy, also known as Soo-nong-gise, Long Horns, is mentioned in Samuel Drake’s 1833 Book of the Indians of North America as a participant in an American attack on Fort George during the War of 1812. He is listed as being in the company of: Farmer’s Brother, Red Jacket, Little Billy, Pollard, Henry O’Ball (Cornplanter’s son) and Captain Cold.

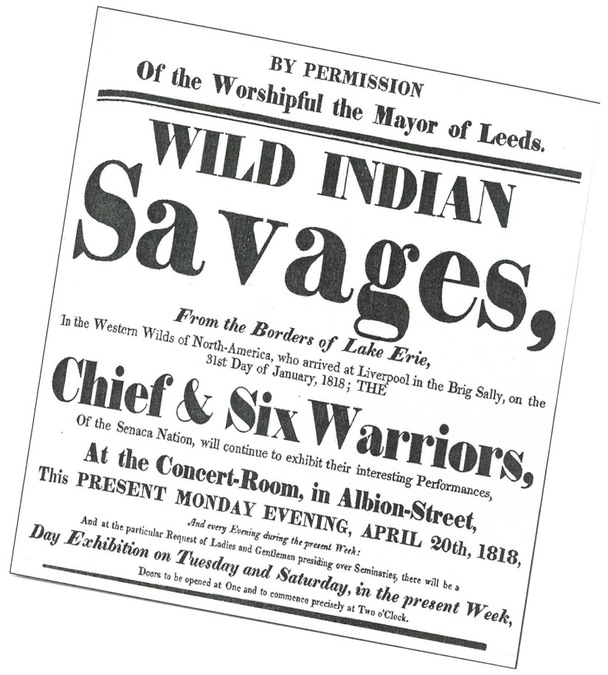

In 1817 a party of Senecas from Buffalo Creek departed for a two-year tour of Europe. They were a chief and six warriors. With an interpreter they traveled by stage to New York City, and then to Boston. With the chief, Tommy Jemmy, “Se-nung-gise,” also referred to as “Colonel Tom,” was the chief’s son, Neguny-awgoli, Beaver; Ne-guye-et-twassaw, Little Bear, the chief’s brother-in-law, and four others. Walter Brigham of Chautauqua contracted the seven to tour major cities of England and Europe, including Paris, entertaining audiences with demonstrations of their manners and customs. As noted in Carolyn Foreman’s 1943 Indians Abroad: “They sailed from Boston on the Brig Sally and exhibited much patience and composure during a stormy and alarming voyage that landed them at Liverpool, England on January 31.”

A handbill promoting the 1818 appearance of the Senecas in Leeds, England.

Carolyn Foreman, Indians Abroad

In 1821, two years after returning from Europe, Tommy Jemmy was arrested by whites on the streets of Buffalo and charged with murder. A near riot ensued at Main and Swan streets. Tommy Jemmy had carried out a death sentence delivered by a Seneca tribunal. An Indian woman named Caugh-quaw-taugh was ordered executed for practicing witchcraft. Red Jacket testified for the defense with a piece of oratory accusing the whites of hypocrisy, reminding them of their own Salem witchcraft executions. The trial and its appeals were a test of Seneca sovereignty, eventually resulting in the complete exoneration of Tommy Jemmy in 1828.

The old chief continued giving performances. He appeared in Boston for the 1841 opening of the Boston Museum and Gallery of Fine Art. Tommy Jemmy’s performance with an entourage was replete with “war whoops and “scalp yells.” Moses Russell recorded his image in an 1841 painting.

The Buffalo artist Lars Sellstedt, in his privately published 1912 biography of William Wilgus, calls the 1849 portrait of the stern, noble and steadfast Tommy Jemmy, “beyond doubt his greatest head.” The Senecas had only recently been swindled out of, and evicted from, the Buffalo Creek reservation. Sellstedt describes the circumstances of the painting as related to him by Wilgus:

“He [Wilgus] went out to the Seneca reservation in Cattaraugus to paint this Indian. He informed the writer that he painted him in a wigwam. Tommy Jemmy, like most all Pagan Indians, never spoke English on occasions of solemnity and ceremony, and it was necessary to employ an interpreter. He seems to have regarded the painting of his portrait as an occasion of more than ordinary importance, for when the head was done – he arose to make a speech. Straightening out his grand old frame of eighty winters, the fierce savage placed himself in the attitude of an orator, his form erect, and his old and rather dim black eye kindling with unusual fire. “Pale painter,” he began, “the Senecas are no longer a mighty nation. Soon they will be no more. The white man will crowd the red man from the earth; our very graves will be plowed up and forgotten. Keep, then, this portrait. Lose it not; give it not away, but put it in some safe place where it may remain forever, that when we are all extinct the white man may see what an Indian was!”