On February 9, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law a bill that would establish what would become, in time, the National Weather Service. Appointed as the first head of what newspapers were then calling “The U.S. Weather Bureau” would be none other than the nation’s Chief Signal Officer, Buffalonian Albert J. Myer.

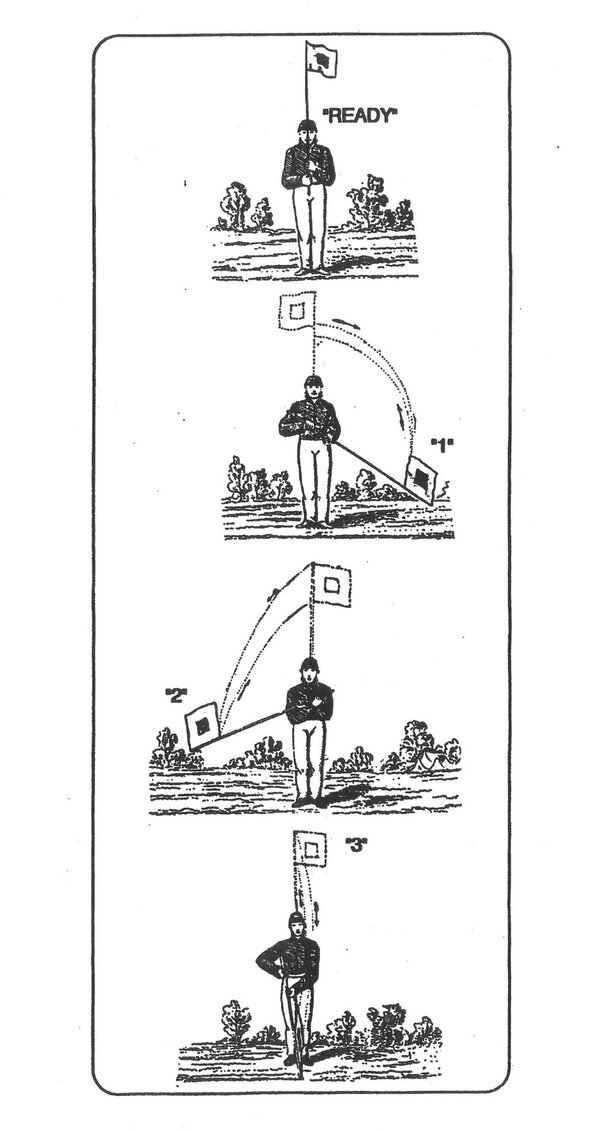

The decision to create a governmental bureau dedicated to the study—and prediction—of weather was born of the fickle meteorological realities of the Great Lakes and the resultant loss of life, particularly in the late fall months. For his part, Myer, who was then a colonel in the U.S. Army, had made his reputation developing a series of visual signals that could be used for a variety of military purposes. These were used to great effect—ironically on both sides—during the Civil War. By day, well-placed members of the signal corps would utilize a series of colored flags and pre-determined motions to convey information over surprisingly long distances. By night, a series of colored lights served a similar purpose.

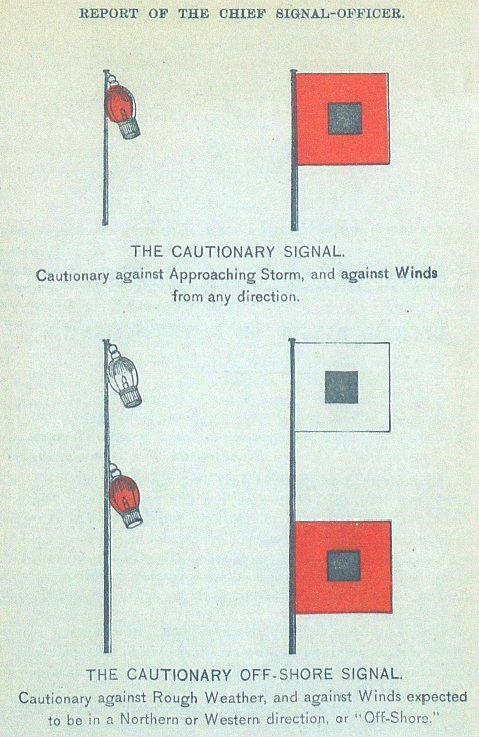

Illustration showing some the use of flags to convey messages, as developed by Albert Myer during the Civil War.

U.S. Signal Corps Museum

Not surprisingly, once in charge of the weather bureau, Myer turned his system of visual signals to the task of warning mariners of impending weather events. Using a series of colored flags, with a different colored center—again with lights used in their place at night—those on the lakes and oceans could be alerted to take shelter in port until dangerous storms had passed. These familiar flags remain in use today, and are most commonly associated with hurricanes.

To warn of the weather, however, one had to be able to know—with at least some level of accuracy—what the weather was going to be. While information on the atmosphere was still limited in the 1870s, Myer enlisted the aid of top scientists to develop methods of weather prediction that landed him the moniker, “Old Probabilities.” The New York Herald made history on May 5, 1871, when it printed the U.S. Army weather forecast for the upcoming 24 hours. This pioneering report prompted another newspaper to predict a futuristic society in which outdoors plans might confidently be made as much as a day or two in advance!

Upon his death in 1880, Albert Myer was laid to rest in the Walden-Myer mausoleum, atop a hill in Buffalo’s Forest Lawn Cemetery. In the aftermath of this past December’s tragic blizzard—which modern forecasters were able to predict with significant accuracy well in advance—it seems fitting to remember that it all started with a Western New Yorker, a century and a half ago.