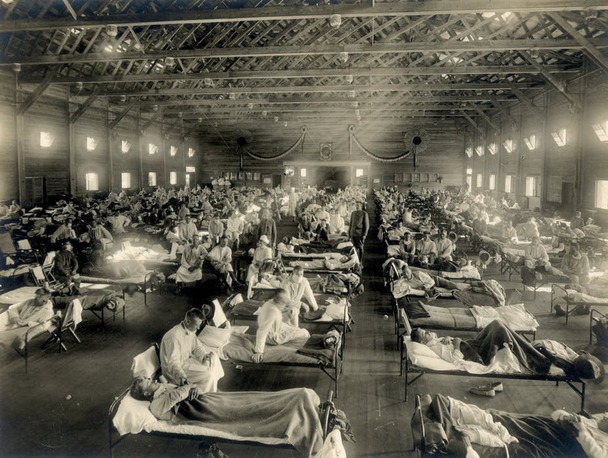

A scene from the influenza pandemic that claimed the lives of 675,000 Americans and over 2,000 Buffalonians.

The 1918-1920 influenza pandemic was unlike any other in recent human experience. The symptoms of the disease were shocking even in a world 30 years or more away from the widespread application of antibiotics: the worst cases would go from walking around healthy to the usual signs of an oncoming flu, to prostration, scorching hot fever, delirium and eventually death in about a week, although some cases progressed markedly faster. Death in this manner was particularly nasty because the flu virus destroyed the lining of the patient’s airways, at which point secondary bacterial infections would infect the damaged tissue. When this happens, the body’s response is to send in volumes of antibodies and lymph. This would cause the patient to gradually drown in their own fluids, after their skin turned a most disturbing shade of lilac. Doctors at the time called it “heliotrope cyanosis.”

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of this particular outbreak of the disease only became apparent once epidemiologists began counting the dead. Unlike the regular seasonal cases of the flu that struck everyone more or less equally, only killing the very old or young, this flu—which, according to the CDC, was “an H1N1 virus with genes of an avian origin”—struck down a huge number of people, even those in the prime of their lives. Exactly why this strain was so fatal continue to be debated. In all, more than 29 million Americans contracted influenza between its first onset in the spring of 1918 and its final wave in Hawaii in 1920. Of that number, 675,000 died from either the disease itself or one of its sequelae, like pneumonia. The pandemic’s death toll exceeded the number of people killed in World War I. In fact, the flu was a major cause of mortality in the war. For every 100 men killed in battle, 102 died of disease, either in the trenches or at bases in the United States. Compared to the rest of the world, the U.S. got off comparatively easy: perhaps as many as a third of the world’s 1.8 billion people contracted the disease—and somewhere between 50 and 100 million of them died. Mortality on this scale is beyond recent human experience.

For Americans, the flu pandemic began in the spring of 1918. In March of that year, more than 100 soldiers at Fort Riley, KS, had contracted the disease and that number would skyrocket in the next week. With America’s entry into the First World War, the following May saw thousands of U.S. soldiers cross the Atlantic for service in Europe. From what we now know about epidemiology, it was likely percolating for months earlier than that, seeding itself thoroughly across the countryside, so that when the disease’s death toll finally rose above the “background noise” of normal mortality and was noticed, it did so nearly instantaneously.

Doctors and nurses attend to dozens of stricken soldiers at Fort Riley, KS. In March of 1918 over 100 soldiers at the camp had contracted influenza and that number would greatly multiply in only a short period.

Courtesy National Museum of Health

Military Beginnings

A second significant military outbreak of the disease was reported in September—this time at Camp Devens near Boston. By the end of the month, nearly one-quarter of the camp had been struck down, with 14,000 cases reported, including over 750 fatalities. This second outbreak was extremely fatal. In fact, within the four-week period of September, virtually everywhere in the continental U.S. was grappling with the deadly disease. Unlike a variety of other communicable diseases like yellow fever, typhoid, trachoma and even glanders, influenza was not a “reportable disease” in New York State at the beginning of 1918. This meant that doctors were not required to report cases to the local health authorities. However, as the ghastly outbreak unfolded a few short hours down the rails in Boston in the third week of September, New York classified the affliction as a reportable disease and created a thorough flu surveillance system. At about the same time, U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue issued a menu of flu control measures that localities were encouraged to enact. These measures ranged from totally quarantining a community and shutting down all places of entertainment, churches, schools and shops to public bans on spitting and mask requirements.

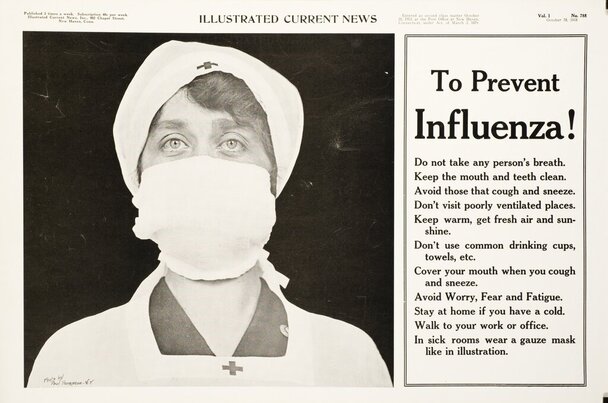

U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue issued a series of flu control measures to localities across the country, in an effort to stem the disease’s spread. But at this time the decision of whether or not to adopt such measures was largely left in local hands.

Library of Congress

Unlike today, when the Center for Disease Control (CDC) operates a sophisticated disease surveillance system with broad-ranging powers to impose public health measures on communities, in 1918 public health was largely the domain of localities. Every large city had a board of health and most states had something similar. These entities were responsible for tracking disease, implementing public health measures and keeping the public informed of both. Their work in 1918 was complicated considerably by the war effort and the reluctance of President Woodrow Wilson’s administration to create any public panic that might interfere with the flow of troops and materiel to the front. Not surprisingly perhaps, this patchwork of administrative authority produced a wide variety of responses among U.S. communities, with Buffalo being on the more thorough-going side. The Queen City eventually enacted the whole menu of anti-flu measures. This, along with what proved to be a fortuitous trolley car strike during the worst of the epidemic, allowed Buffalo to escape with a relatively light outbreak.

With a population of 475,000, Buffalo was the nation’s tenth largest city in 1918. Although the grain transshipment and associated industries that had made Buffalo’s fortune were under threat from the Welland Canal, the city was home to a variety of industries vital to the allied war effort that continued to spur growth. Specialty industries like the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, several car and truck manufacturers and a slew of casting and machining businesses all made important contributions to the world’s first attempt at mechanized war. Along with the shift away from reliance on Midwestern grain, there was a massive social shift underway as well. The predominantly Irish immigrants who had scooped the laker’s holds into the silos along the waterfront gave way to the new wave of immigrants in Buffalo. This second wave was made up mostly of Poles and Italians, who commonly worked as low-skill industrial laborers in 1918. These immigrants arrived at the very bottom of a social structure that lacked any of the safety nets we have today. Their housing was frequently haphazard, crowded and unavoidably filthy. Their employers’ attention to worker welfare and safety was astonishingly callous, leading to both industrial disease and lower overall health for factory workers. These factors together led to a well-documented drop off in health, fertility and life expectancy among new immigrants. These newcomers also had an increased susceptibility to contagious disease. Given these realities, it is perhaps unsurprising that the first reported cases of influenza in Buffalo were in the 10th and 15th wards on the East Side, which were heavily populated by immigrants.

The changing demographics and industry of Buffalo were only two of the changes rocking the Queen City. Technology was remaking society at a pace unheard of previously in human history. Buffalo’s theatre district was already well established in 1918 and saloons, pool rooms and bars had a long history, especially in working class neighborhoods. There were new sights to take in as well: Buffalo was home to the nation’s first purpose-built movie theater, the ‘vitascope hall’ in the Ellicott Square Building, which opened on October 19, 1896 (and saw an astonishing 200,000 visitors its first year despite having only 72 seats!). By 1920, the Chamber of Commerce listed at least eight theaters, providing low-cost entertainment for Buffalonians of all classes as well as a nearly ideal environment for the spread of flu. The streetcar system was well established in Buffalo by 1918, with over 415 miles of track laid within the city and the suburbs. This drew the city into one cohesive whole and allowed the spread of disease in crowded streetcars, as well as the rapid movement of disease from one locale to another.

A bustling downtown Buffalo—complete with shops, schools, theaters, saloons and streetcars—presented, like many other urban centers nationwide, ideal conditions for the flu to spread.

Western New York Heritage Collection

The Queen City in 1918

The appearance of the flu created demographic and technological upheaval in Buffalo at the end of September. The Buffalo Enquirer reported influenza at Niagara-on-the-Lake on September 21, where the disease had sickened “over 300 soldiers in training in the Polish division of the cantonment…and is rapidly spreading to other divisions in the same camp.” The following day the first cases were reported in the city—three people with the flu were seen by doctors and those doctors reported the illness to acting Health Commissioner, Dr. F.C. Gram. The disease had almost certainly been percolating in Buffalo for several days by that point.

When a person contracts the flu, they are contagious for two to four days before symptoms begin to appear. Thus, those first three sick people in Buffalo had already likely infected dozens more at work, at school, on the trolley or in their crowded apartments. They were spreading the disease in ever-widening ripples across the city. Dr. Gram sounded a cautious note, suggesting that his agency was running down the people possibly infected and that there were effective preventative measures available. He also asked school teachers and factory foremen to report any sick individuals to the City Medical School Examiners. All official pronouncements on the flu were muted in an effort to avoid public panic. That said, Gram did mention that the war and the epidemic already raging in Boston had virtually stripped Buffalo of medical professionals, saying: “I would not know where to get either doctors or nurses in Buffalo in case of emergency, for a majority of them are overseas.”

Two days later, the flu showed up in the U.S. Naval Barracks on Chenango Street, where 16 sailors fell ill out of the 400 quartered there. The medical officer in charge, Lieutenant Otis Chase, immediately quarantined the sailors and announced that, “I do not believe that the jackies are suffering from the real Spanish influenza…the malady resembles the old fashioned grippe of 20 years ago.” The ever-cautious Gram publicly agreed that it wasn’t the flu.

The first two deaths officially attributed to the flu happened two days later, with a mother and her 12-year-old daughter passing only a day apart of each other. Reliably, Gram pointed out that there was no clear evidence that it was Spanish Flu that killed them, but for the first time he mentioned that his department was considering a plan to be mapped out “to fight the disease if it develops in Buffalo.” It is now clear how much of this calm was part of an intentional public relations campaign on the part of Dr. Gram as the acting health commissioner. Gram was aware of the danger, as he had made the flu reportable on September 20 and the following day announced that he had devised a plan to fight influenza. As part of his campaign, Gram distributed a bulletin from the U.S. Surgeon General that described the flu and several basic preventative measures.

Bulletins and posters, like this one from Connecticut, were disseminated in an attempt to educate the population on measures to prevent the spread of influenza. Buffalo acting Health Commissioner, Dr. F.C. Gram, added to the Surgeon General’s warnings a paragraph detailing how to handle the corpses of anyone dying from the disease, including immediate burial in an unopened casket.

Courtesy U.S. National Library of Medicine

The Flu Comes to Buffalo

Throughout much of the following week the drumbeat of death notices continued, but the Buffalo newspapers did not run any follow-up on Gram’s “investigations” into the cases of the flu or on his plan for combatting it. On October 3, a photograph of nurses wearing gauze masks prepared to treat soldiers and sailors in a military hospital in Boston appeared in the newspapers. Presumably, this was somewhat shocking to readers—something akin to our modern reaction to images of space-suit-clad doctors caring for Ebola patients in Liberia—but no doubt it was also meant to be instructive. The picture was a profile view that clearly showed how to tie a mask.

The following day the workers of the International Railway Corporation (IRC) declared a strike after failing to obtain a raise. Although this spelled disaster for the factories, schools and businesses of Buffalo, as well as the citizens who had to scramble to find alternative means to reach them, it closed a significant vector of infection. It also eased crowding in downtown, effectively isolating anyone whose business didn’t merit jitney fare or a long walk. The same day, U.S. Surgeon General, Rupert Blue, issued the suggestion that municipalities close schools, theaters and most controversially churches, effective immediately. For the first time, a note of concern was sounded by a member of the executive branch. Surgeon General Blue mentioned that 1,040 soldiers and sailors had died, mostly of flu or pneumonia in stateside camps in the last week, up from 172 the week previous.

By Tuesday, October 8, the news announced that 122 new cases of the flu had been reported and that a total of 456 cases and 33 fatalities had been reported to Dr. Gram since October 1. In this context, Gram first floated the idea that Buffalo may have to submit to a quarantine. First, however, he met with Mayor George Buck and the city corporation lawyers the following morning to determine whether or not he had authority to carry out his threat. No doubt their affirmative decision was influenced by the fact that 160 new cases had been reported by noon that day. As a result, Mayor Buck issued an edict on October 10 closing churches, theaters, schools and “places of public assemblage,” effective 5 a.m. on Friday, October 11. Buffalo was officially quarantined, although factories continued full production, as did other businesses. Many, however, required their workers to wear masks and keep windows open while they worked. The Buffalo Evening News led with a piece describing Buffalo the following morning as “…a community without street cars, theatres, saloons or schools—a situation unique in its history as a city.”

Buffalo’s old Central High School on Niagara Square (at right of photo) was hastily converted to a 1,000-bed emergency hospital in an effort to contain and care for Buffalonians who had contracted influenza.

Western New York Heritage Collection

A City Under Quarantine

Public funerals were specifically banned. The Catholic Church reported that a priest would say daily masses, but that their parishioners were barred from attending. Outdoor church meetings were initially allowed by Dr. Gram and Mayor Buck, but when October 12 dawned cold and rainy, Dr. Gram forbade them, saying that, “If all churches in Buffalo were to hold outdoor services on Sunday, we would have at least 50,000 additional influenza cases by Tuesday and possibly 1,000 more deaths by Thursday.” Interestingly, meetings of the street car union were the one exception to the ban, with the caveat that they be held outdoors. Grimly, Gram also reported that 690 new cases had been reported since noon on October 10 and that a further 42 people had succumbed to the disease.

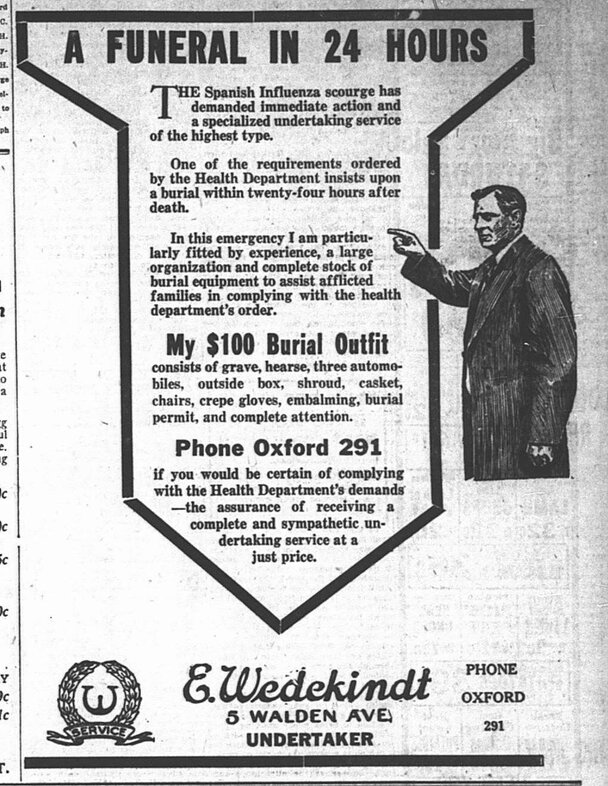

Over the weeks that followed, the famed Italian tenor Enrico Caruso canceled a concert in Buffalo, a terrier dog show was closed early and eagerly anticipated football games failed to be played, while meetings of an association of advertisers and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) were halted. Citizens were told to stay home when sick, wear masks, stop spitting in public and stop shaking hands. Private Arthur Poole succumbed to the disease at Camp Custer in Michigan before he could test his bravery against the Kaiser’s guns. George Fraley Jr., a scion of high society and a semi-pro golfer, died at the age of 18 before he could enter the class of 1922 at Yale. Ernest R. Goat, who made his living selling Chevrolets to the people of Buffalo, died and left behind a widow and two children, one of whom was also dying of the flu. Meanwhile, the funeral home of Ernest Wedekindt advertised, “A Funeral in 24 Hours” and his “$100 burial outfit consist(ing) of grave, hearse, three automobiles, outside box, shroud, casket, crepe gloves, embalming, burial permit and complete attention.”

Funeral director Ernest Wedekindt offered a special funeral package for flu victims in October 1918.

From The Buffalo Courier October 18, 1918

The epidemic peaked in Buffalo between October 13, with 1,882 cases reported, and October 19, when 119 people died in one 24-hour period. On October 27, the International Railway Corporation gave in to employee demands and raised the men’s pay to 46 and 48 cents an hour, allowing them to turn on the heat in the cars and also to pay some $275,000 in back pay. The car men agreed to the deal outdoors, of course, at the Buffalo Baseball Park. Car service resumed that afternoon, although with strict mask and open window requirements imposed by Dr. Gram.

The quarantine was officially lifted at 5 a.m. on November 1, although churches were allowed to hold services (with parishioners included this time) at noon the day before. With the resumption of streetcar service, the continued decline of flu cases and the subsequent lifting of the quarantine, most of Buffalo’s citizens settled back into the pattern of Liberty Loan drives, newsreels of the war and work. Students were spared making up all of the class time they missed by Superintendent of Schools Ernest C. Hartwell, who added a half hour to each remaining school day and argued that, “Those in charge of making out Regent’s examinations [will have] to make them easier this year.” A small notice, consisting of two sentences, well below the fold on November 8 declared, “Influenza is no longer epidemic in Buffalo.” Three days later, the war ended and the world definitively moved on—or so it would seem. A third wave of influenza would hit the United States during the winter and spring of 1919, including over 700 cases reported in New York City (with 67 deaths), but this wave would falter with the coming of summer.

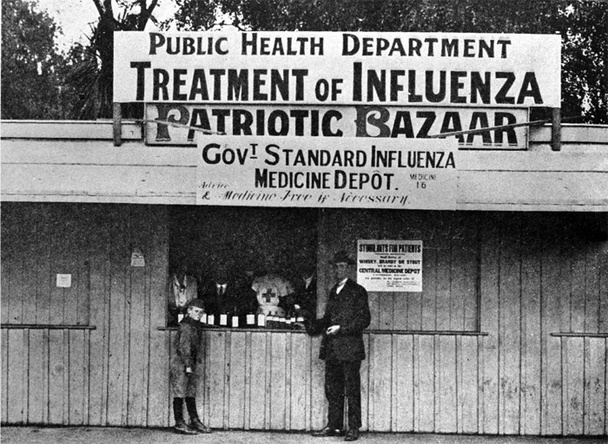

Public health booth in Seneca County—one of many that were established around Western New York in a frantic effort to treat victims of the influenza epidemic, as well as attempt to stem the disease’s spread.

Private Collection

The influenza pandemic was a private tragedy that occurred during a time of great and very public tragedy and triumph in the First World War. Thousands of Buffalonians died of the disease or its complications, a 31.4% increase over the previous year. Almost all of the fatalities occurred in the brief period between the end of September and the beginning of November 1918. Social norms within Buffalo broke down quickly; one of the city’s Polish-language newspapers reported that priests were doing funerals assembly-line style, blessing a stream of caskets as they passed in front of the church. The Erie County Sheriff had to serve notice on St. Stanislaus to force the church to bury corpses left in the open. In order to comply, they had to hire 35 additional gravediggers. The flu created thousands of orphans, rearranged countless families and, of course, ended the lives of 2,388 Buffalonians, 61,700 New Yorkers, 675,000 Americans and at least 50 million worldwide.

Many in today’s world of antibiotics and advanced science fail to grasp just how deadly the flu was a century ago, leading to one of its many names: America’s Forgotten Pandemic. That moniker is somewhat misleading, however. Mention the flu to any group of people and it is likely that someone will report they had a grandparent, or increasingly, a great-grandparent, who died of the flu. These stories expose the myth of a forgotten pandemic. Of course, it could also be that Buffalo had an additional reason for forgetting, in that the comparatively strict quarantine served its purpose. According to a 1919 report, of the city’s 475,000 residents, a total of 28,398 were sickened. This works out to a morbidity rate of about 6 percent, far less than the ten percent national average.