Colonel Peter A. Porter made this sketch of the Old Stone Chimney and one of the 19th century dwellings to which it was attached.

From Benson Lossing’s Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812, 1868

Most Western New Yorkers have never heard of

When, in 1759, the British drove the French from the

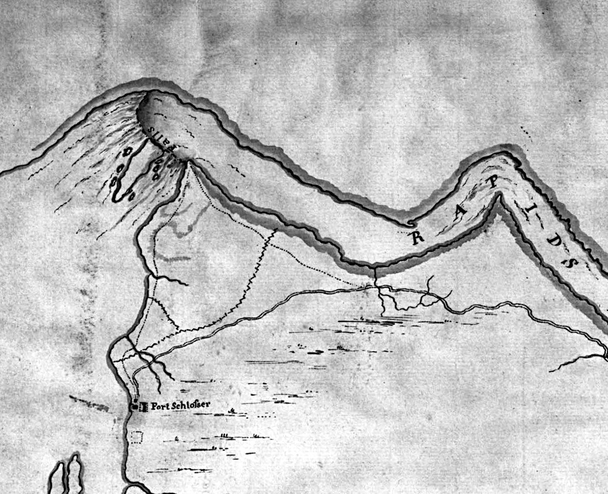

This detail from a 1788 by British engineer, Gother Mann, shows Niagara Falls, a portion of the Portage Road and the location of Fort Schlosser (at lower left). Note the dotted outline of the older French fort just below Schlosser.

Courtesy Library and Archives Canada

In 1796, the British finally relinquished their control of the region under the terms of Jay’s Treaty. Soon after, American brothers Augustus and Peter B. Porter, along with Benjamin Barton, purchased strategic land holdings along the

The Old Stone Chimney has stood alone for more than half of its lifetime. The effort to preserve it is more than 130 years old, though the argument could be made that it actually dates back over 250 years if one considers Stedman’s original repurposing in 1761. In 1880, the Hon. Peter Augustus Porter, grandson of Peter B. Porter, inherited the old Stedman farm, about the same time that the last house erected to incorporate the chimney was torn down. Porter had lived in that house for a couple years during his childhood along with his father, Col. Peter A. Porter, who perished at the Battle of Cold Harbor in 1864. Peter Augustus placed great value on the history of his pioneering family and was in a unique position to preserve the legacy of the Niagara Frontier at an important confluence of American thought and ideology. Following his graduation from Yale, he fixed himself upon the task of amassing the single most comprehensive library of the history of the Niagara area and, after retiring from public service as a U.S. Congressman, set about writing dozens of articles, books, pamphlets and public speeches that documented the history of the region.

This rare early photograph of the chimney, ca. 1895, shows the buildings of the Adams Power Plant in the background. The interests of power and industry would jeopardize this artifact for over a century.

Courtesy Niagara Falls Public Library

During the late 19th century, plans were made for the final setting for this storied piece of

Peter Augustus Porter was keenly aware of his family’s role in the history of the Niagara Frontier and worked tirelessly to preserve and protect the Old Stone Chimney.

From Peter A. Porter, The Niagara Region in History, 1895

Peter A. Porter sold the old Stedman farm to the rapidly growing Niagara Falls Power Company in 1890. As it became increasingly apparent that this tangible connection to frontier and colonial history would surely be lost to the electro-industrial age, he arranged for the company to move the chimney. The structure was moved about 150 feet in 1902, though not to the spot Porter had envisioned and Olmsted had partially articulated. In fact, the move only temporarily placed it out of harm’s way. Even so, those managing the relocation process took great pains to mark and replace each exterior stone precisely. C. Breckenridge Porter oversaw this move for the Niagara Frontier Historical Society, the organization his father, the Hon. Peter A. Porter, founded in 1898.

The Niagara Frontier Historical Society placed a bronze plaque to “landmark” the Old Stone Chimney in 1915 to great public fanfare. Among the speakers, Frederick Lovelace, the secretary of the Niagara Falls Power Company, publicly asserted “…a sacred trust to preserve inviolate as long as time and the elements will permit what now remains of this old fort, an object of so much of interest and of import to the history of the State of New York.” He continued, adding that “the Niagara Falls Power Company takes this opportunity to assure the society that at all times it will cooperate in protecting and preserving this hallowed relic of a glorious past.”

The chimney has been moved several times in its history, as part of efforts to protect this important link to Niagara’s early European history. Here a scaffold has been erected around it to allow workers to carefully number and disassemble the chimney for removal to the new Porter Park. The photo clearly shows the encroachment of the Carborundum Company in the 20th century.

Courtesy Niagara County Historical Society, Daniel Dymuch Collection

Unfortunately, the 1902 move did not account for public access needs or the further industrialization of the location. In 1942, the Carborundum Company (which had acquired the former “upper landing” site about 1895) grew rapidly, increasing its footprint many times over. Again, the chimney was in danger of being destroyed, this time by the wartime demand for abrasives produced by the company. Carborundum and Niagara Hudson, successor to the Niagara Falls Power Company, split the considerable cost of moving the Old Stone Chimney. Again, workers carefully marked stone-by-stone the location of each, and reconstructed it exactly. This time, however, a plan was followed to place the structure in an area where the public could access the relic without molestation. It was placed in view of the shores of the Niagara River, and proudly bore its bronze plaque in an appropriately named “Porter Park.”

Today, the Old Stone Chimney remains at Porter Park – or what is left of it. The area has changed so much over the last half century that the chimney now stands in utter obscurity. Porter Park was largely developed during and after the construction of the Niagara Power Project (1957-1962). The collapse of the Schoellkopf Power Plant in 1957 brought the need and opportunity to build a modern power station, one that took full advantage of

Porter Park was further parceled and paved in 1972 to provide a parking lot for the Moore Business Forms facility at

The Moore Business Forms facility ceased operation in 2011, an event that quietly restored some visibility to the old relic. However, the imminent reconfiguration of the Robert Moses Parkway now places the Old Stone Chimney at risk once again. Efforts are underway to bring stakeholders to the table and provide for the preservation, public access and interpretation of this important artifact. With these efforts come an opportunity to spur economic development, while preserving the important history of the old Niagara Portage and the many events to which it bore witness.